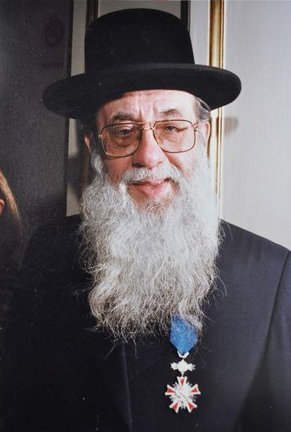

Rabbi Mendel Reichberg Z”l

Not so long ago, RABBI MENDEL REICHBERG had to beg people to make a minyan in Lizhensk. Today, traveling to the NOAM ELIMELECH’S KEVER has become the trip of the year

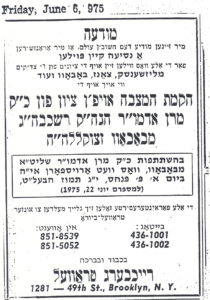

The posters advertising the trips to Lizhensk for the Rebbe Reb Elimelech’s yahrtzeit on 21 Adar are a travel temptation. Mens’ trips, ladies’ trips, groups from New York, from Israel, from Europe; see Cracow and Warsaw and Lancut and Belz, or just come straight back; mehadrin meals, five-star accommodations, online check in. But just 48 years ago, visiting the gravesite of the heilige Reb Elimelech was an impossible dream.

In Tammuz of 1974, the Bobover Rebbe, Reb Shloime, asked his loyal chassid — a travel agent named Rabbi Mendel Reichberg — to arrange a trip to Poland so that he could go to the tziyun of his ancestor the Divrei Chaim of Sanz on the yahrtzeit. Poland was still under Communist rule, and the arrangements were far from simple.

Rabbi Mendel Reichberg z”l, who was born in Bochnia and learned in yeshivah in Cracow, had himself visited the kever of the Noam Elimelech when he was young, which left an indelible imprint on his soul. After surviving the ghetto and the camps, Reichberg immigrated to the US, where he opened a travel agency. He was an old-time Yid who remained very close to the Bobover dynasty, and while he rebuilt a family and created a business, he never forgot the tzaddikim of Europe whose graves had been so callously destroyed and lay abandoned. During the 1950s and ’60s he made a few solitary trips to daven at the kevarim in Poland, hanging notices in the shtiblach in Boro Park before each journey, with an offer to take kvittlach for anyone who wanted.

“In those years, you had to apply for visas at the Polish embassy in Washington, D.C.,” says Reb Mendel’s son, Wolf Reichberg. “Later they opened a consul in Manhattan. Each person who wanted to travel to Poland gave my father their passport, and filled in a form with all their details, the purpose of their visit, and where they would be staying. My father took these to the embassy to apply for visas, which took about two weeks. Those who wanted to join from Eretz Yisrael had to send their passports to New York for my father to take care of their visas.”

All foreign tourists had to prepay at the embassy in advance of their stay in a government-owned hotel, where their rooms were carefully monitored, and when Rabbi Reichberg rented a bus, two Poles came along: one driver and one secret-service agent, to keep an eye on the doings of the foreigners.

Rabbi Reichberg made arrangements for the Bobover Rebbe and his entourage — about 120 people in all, including Rabbi Reichberg and his sons.

“It was the first time the Rebbe had been back to Bobov since his family was expelled. Before the war, his father Rav Bentzion had been rebbe there, and he had served as the rav. Rav Bentzion was murdered, the entire community was gone, and here he was, coming back as Rebbe, to visit the kever of his great-great grandfather, the Divrei Chaim of Sanz, and walk through the village from where he ran for his life. The Rebbe walked through the streets of Bobov, accompanied by his brother Rav Yechezkel Dovid Halberstam and some older chassidim who had lived there, reciting pesukim from Eichah and Tehillim.

Admor M’bobov Zt”l with R’ Mendel Z”l

The locals came out to see the visitors. “It had been more than 30 years, but when they saw who it was, they started to call out to the Rebbe, ‘Shloimka! Shloimka iz du!’ ” Wolf remembers. “Then they started to sing what they remembered from the chassidishe chasunahs before the war — ‘Kol rinu viyeshiuh be’uhulei tzaddikim’ and they sang in Yiddish ‘der Rebbe zohl leben a mazel tov, alleh chassidim a mazel tov, alleh goyim a mazel tov, un a mazel tov.’ ”

After walking through the shtetl and visiting the area of the hoif and the old Bobover shul, which was still standing, the Rebbe and his brother went into what had been the backyard. Wolf Reichberg went with them. They were looking for something specific, something which they had buried underground before they had been forced to leave Bobov: their Zeide the Divrei Chaim’s menorah and shteken (stick).

“The Rebbe knew exactly where he had hidden it, but the Poles had built a house on that spot. It seemed irretrievable, and he did not want to approach the non-Jews to inquire about it,” says Reichberg. The holy menorah and shteken were gone, like the rest of the world of prewar Bobov.

Time to Renew the Custom

The following year, in Adar 1975, Rabbi Reichberg decided that he wanted to take a group of people to Lizhensk for the Noam Elimelech’s yahrtzeit. “My father began to call people up and ask if they wanted to join. There were no takers. Many older people felt afraid and didn’t want to go back to the “blittige land” — the blood-soaked country where their families had been killed. But my father had strong feelings for Lizhensk, and he felt it was time to reinstate the custom. He had no fear of going back to Europe — ‘What can they do to me that is worse than what Hitler did?’ — Eventually he had a group of eight people with him. The following year, 1976, there were 20 Jews from America. After that, the crowd soon grew to a hundred, then to thousands.”

Rabbi Reichberg took the group to the Bochnia ghetto. In the town’s marketplace, a crowd gathered around as he showed his sons Mayer and Wolf the area where his family had lived. “The group of Poles got bigger and bigger, and my father turned to them and said ‘See, nobody killed us, we Jews are still around. We live in America, and there are plenty of us, and we’re doing well there….’ The police came over to disperse the crowd then, they told us that we were not allowed to talk to the local populace about America, since it could open up their minds and create anti-Communist feeling or even a revolution.”

Poster to lizensk in 1975

During those early trips, there was such an atmosphere of suspicion that the Reichberg group did not interact even with other Jews whom they met there, for fear that they were government agents. The Polish Communist government kept a very close eye. “They used to come and snoop on us as we davened at the kever in Lizhensk. They were tzittering from us. Were we exchanging money? Bringing in counter-revolutionary literature? They opened up the kvittlach to read them and see what we were up to.”

But with time, it became clear that Reichberg’s group was doing exactly what it claimed to be doing: praying. The government began to relax and eventually even removed the requirement for visas. Eventually, in 1997, Rabbi Mendel Reichberg received The Order of Merit of The Republic of Poland for his involvement in tourism and regeneration of Jewish sites.

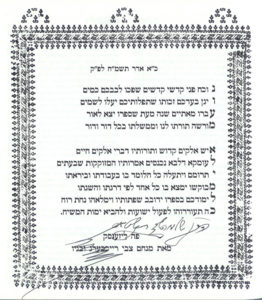

Letter from Rabbi Reichberg Z”l

On his travels, Rabbi Reichberg noticed the appalling state of many of the gravesites. In many places, the cemeteries were in danger of being built over. His son, Mayer, said to him, “If you don’t do something now, the next generation will build houses on this spot,” and recognizing the truth of this, Reb Mendel acted to protect the kevarim in Riminov, in Koznitz, in Lancut, and in Ropshitz.. He designed impressive gates and fences around the cemeteries to mark the sites, and rebuilt the structures around the graves of the tzaddikim so that people could come and pray there. Every year, during Aseres Yemei Teshuvah, even as he aged, Rabbi Reichberg traveled to Europe by himself with a cache of 10-day candles. He didn’t want the holy shuls and kevarim to be without a lecht burning over Yom Kippur.

Today, the number of participants on trips to Europe has exploded, and includes tours for women as well. “The next generation has no fear of going to Poland — they never experienced the terror,” says Wolf Reichberg. “We now provide tour guides, and we spend an inspiring Shabbos together. Today, there are beautiful hotels, but in my father’s pioneering days, he bought a kitchen and an oven which he kept there in storage, and brought all the food with him.”

Today, the trip is one of the year’s inspiring highlights for thousands; any taxi driver in the area can take you to the Noam Elimelech’s kever. And it all started with Rabbi Reichberg begging for a minyan to join him.